2018 Google.jpg)

Rivers and Roman Roads in Hampshire and the west of Sussex

Image Landsat / Copernicus, (c) 2018 Google

A Whiteparish local history page from younsmere-frustfield.org.uk

This page has its origins in a talk I gave to the Romsey Archway U3A Local History Group on 15th October 2018, to whom I'm grateful for the incentive this gave me to collect and refine my notes on this topic.

Aethelweard's Chronicle relates how Cerdic and Cynric landed in 495 with three ships at Cerdic's Ora, a bank or shore believed to have been at the head of Southampton Water and later associated with the Netley Marsh area. There is also a doubtful enclosure bank near the shore near Calshot that is sometimes claimed to lie near a spot on the coast there at which he landed. This page explores their slowly expanding territory known as Netley from 508 and as the kingdom of the West Saxons from 519. Following the account from Aethelweard's Chronicle and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles supplemented with deductions from place names, later county boundaries, hill forts and earthworks such as Bockerley Dyke and Wansdyke, a tentative account of this expansion is offered here. This has been attempted many times, but here the focus is on developing a likely background from which to assess how Whiteparish is likely to have been affected by events in the subsequent centuries. Broadly Whiteparish was probably just outside the 508 area of "Netley" and within the territory gained from the Atrebates in 552 with the successful West Saxon attack on Old Sarum.

For the West Saxons landing at the head of Southampton Water in 495, the landscape they saw would have been dominated by the major rivers and the Roman Road network. The roads would have provided easy ways of travelling quickly both for them and for the local Britons, but early Saxon settlement was almost invariably alongside navigable water. This map shows the main rivers and Roman roads in an area centred on Southampton, along with modern county boundaries and towns. All of these will feature in this story. To the right the Saxon kingdom of Sussex already existed. The Meon valley through Soberton would be taken by Jutes friendly with the West Saxons, as would the southern part of what is now the New Forest along the coast through Lymington and New Milton. The boundaries of Hampshire with Dorset and Wiltshire would be significant checks against initial expansion, well defended as they were by the post-Roman Britons, the Atrebates to the north and the Durotriges to the west, from which the modern attributions of Attrebatia and Durotrigia stem. From Southampton the Saxons would move west to the river Avon north of Ringwood, incorporate the Jutes and take the Isle of Wight in an initial period of consolidation before breaking out northwards.

This is the most importantly the story of early Wessex from the initial landing in 495 to 556 when the West Saxons advanced to join forces with the Gewisse, who had setted in the Thames Valley around Dorchester-on-Thames. Having covered the early years, this page will give a brief summary of the progress of Wessex up to the establishment of the Danelaw by King Alfred, following his defeat of the Vikings at Edington in 878. As well as helping set the events of the early years into context in the broader development of England, it will provide further useful context for likely events in the area around Whiteparish.

2018 Google.jpg)

Rivers and Roman Roads in Hampshire and the west of Sussex

Image Landsat / Copernicus, (c) 2018 Google

As the second half of the fourth century progressed a number of changes were seen across Roman Britain. Seemingly coordinated attacks resulted in a slow shift away from urban life, the reinstatement of pre-Roman defence lines and the gradual decline of the money economy. Problems on the continent, together with discontent and discord within the Roman legions led onwards towards the letter from the Emperor Honorius in 410 telling Britons they would have to look to their own defence.

The following 35 years saw the re-emergence of a regional system of government closely following pre-Roman tribal boundaries. Angles, Saxons and Jutes then progressively pushed the Britons back from the south and east coasts over the course of some 130 years.

The timing of the establishment of the main British kingdoms

Note that there is more detail for the southern kingdoms

Along the south coast, Kent and Sussex were swiftly and effectively taken and populated by Jutes and Saxons respectively. In strong contrast, the establishment of Wessex as a major power took a very long time. This is its story.

The timeline below shows the end of the Roman period in 410 and the landings in 495 that were to result in the establishment of a West Saxon royal family in 519.

A simple timeline for the end of the Roman period and start of Wessex

Cerdic was king of the West Saxons from 519 to 534

By way of a spoiler and to help give structure to this page, the next diagram shows one local historian's view of the development of Wessex from 495 to 625. The Isle of Wight, here shown occupied by the Jutes from an early date (red), is joined by a small Saxon area around Southampton Water. Further north the Gewisse occupied a small area in the upper Thames valley around Dorchester. Wessex really started to expand once these two groups of related Saxons joined forces around 556, here shown as slightly earlier. If time permits I'll briefly follow the thread onwards to Alfred the Great and the division of England between Wessex and the Danelaw.

Early expansion of Wessex 495 to 625

Before setting out on this journey, however, a brief look at the sources I've used.

The earliest documentary source from Britain is by the British Monk Gildas writing in about 540, and a full two centuries later Bede wrote his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. Then there is a complex set of documents referred to as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Written in the reign of Alfred the Great towards the end of the ninth century, the original was copied and distributed to monasteries across England. Earlier local records were added to many of these, especially in Wessex, and most were added to from year to year, the last entry being for 1154. There are nine versions still existing, none being the original. The figure below shows the way in which they appear to be connected and where Bede and Gildas were used as source material. Other related documents shown include Asser's Life of Alfred, Aethelweard's Chronicle, the Mercian Register and the Northumberland Annals. Two rather fanciful histories are generally relegated to the fiction shelf of the library, these being Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Britanniae (De gestis Britonum) of 1136 and Nennius' Historia Brittonum of 828, but surviving only as copies dating after the 11th century. These are the source of the King Arthur tales. There are also a number of relevant documents from the continent that confirm various details.

Illustrating the main British and Saxon documentary sources

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles themselves and documents containing material from them are marked ASC

Seax and Gew show whether the term West Saxons or Gewissa is used in the document

Red lines show where material has been incorporated from an earlier document

These documents have been studied to death, of course, and many historical accounts rely on them. The story of Wessex has been told many times over hundreds of years by historians, archaeologists, antiquaries and with the advent of the web by a host of local historians. Together these set out a truly amazing range of different accounts of the conquest. While the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles provide a simple and straightforward timeline, this has been used, reused, modified and even completely denied as a plausible account of events. In some of the more extreme versions it has been argued that:

I've taken a more accommodating line here, comparing the written accounts with other information. County boundaries, hillforts, defensive earthworks, early place names, geographical features and later cultural association of groups of people all add verisimilitude to the written account, filling in some of the gaps and predictably throwing up a few new questions and challenges. My conclusion is that the written accounts are both feasible and credible, even though they had been passed on by word of mouth for many generations before being committed to the pen.

The boundaries and identities of the Iron Age tribes before the Roman conquest strongly influenced the division of Britain after the Romans left, so let's look briefly at our area in those times. The first map shows the wider pattern across southern England and the next one focuses on the main area of action for early Wessex.

Approximate Iron Age tribal boundaries 100 BC to AD 43

The Belgae and Atrebates, related tribes from northern Europe, arrived in Britain as Julius Caesar pushed north around 100 BC, as did the Regnenses in Sussex to the east. Popping across the channel to escape new invaders has a long pedigree. To the west the Durotriges were to put up a fierce resistance to the arrival of the Romans, and would in due course hold back the Saxons in like manner. Their close network of hill forts were to play a key part, as were their linear earthworks at Bokerley Dyke and Wansdyke, both still impressive barriers today. The area the Belgae and Atrebates occupied in southern England would closely define the area occupied by Wessex by 577, 80 years after their landing, modified by the purple line defining a new Durotriges boundary after the Romans left. This purple line broadly follows the Salisbury Avon north to meet the east-west line of the Wansdyke. Even after the Belgae and Atrebates had fallen, the Durotrigies held the Saxons broadly to these boundaries for a second period of 80 years until 658.

A closer view of Iron Age tribal boundaries 100 BC to AD 43

At the top edge of this map, the boundary of the Dobunni intrudes at the top left and the Catuvellauni at the top right. These areas were eventually to become part of Mercia. To the right of this map another tribe, the Regni (also Regnenses), invaded what is now Sussex across the Channel in 100 BC as Julius Caesar advanced. The Regni, Atrebates and Belgae were closely related tribes with a presence after 100 BC on both sides of the Channel.

The Romans invaded through the Isle of Thanet in Kent and seem to have established a military base and supply depot at Fishbourne in Sussex. The Cantii, Regni, Belgae and Atrebates were pro-Roman, but the Durotriges put up a fierce resistance in Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall.

During Roman times it is almost as if there were two parallel cultures in Britain, especially clear cut in the south of England. On areas of high land the Romano-British continued an existence very similar to that of the late Iron Age, cultivating crops and livestock. On lower land and in significant valleys the "villa" economy prevailed, with each villa the centre of a farming estate. Apart from the legions themselves that kept law and order, there were relatively few non-British Romans, if I can use that term.

In the years immediately before the Roman Conquest, Iron Age people were starting to establish villages close by their hill forts, and the widespread development of towns and villages in Roman times is a key feature of the period.

As the Roman period neared its end the Roman peace was progressively tested. The period between 364 and 368 saw attacks by Scoti, Picts, Saxons and Attacotti, as well as Roman military deserters and indigenous Britons. There was dissention at the time in the Hadrian's Wall garrison, doubtless a contributing factor [see Wikipedia and Wikipedia].

Because the hostile forces could move quickly and easily around the Roman Road network, this event had widespread repercussions. At the point where the Dorset, Wiltshire and Hampshire boundaries meet today, the old Iron Age Bokerley Dyke had been cut midway between Old Sarum and Badbury Rings by the construction of the Ackling Dyke Roman road. The Dyke was brought back into use shortly after 364, cutting the Roman road, and there are Roman remains that suggest that the Iron Age hillfort at Badbury Rings had been partially brought back into use, presumably by the nearby inhabitants of Vindocladia, a village close to the hillfort that started before the Roman period and was an important Roman town. It seems probable that at least some of the hillforts started to be reoccupied in this period in Romano-British areas.

Invasions in 383 to 410 from

this Wikipedia article

An early view of origins and destinations in the 5th century (Bede adds Jutes in Ytene, Meonwara, Isle of Wight, but a few years later) [Wikipedia]

Key Roman towns and settlements in the area are well documented - the Roman fort at Clausentum (Bitterne), the settlement found in 1880 near Netley, Old Sarum (?Sariodunum), then Silchester to the north and Chichester to the east. The main tribal areas were each represented by a central town - ??? Atrebatum, /// Belgae, ??? Durotriges, ??? Regnenses

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (ASC), the story of Wessex starts in 495. Other kingdoms had been swiftly taken after the Romans left, Kent by Hengist and Horsa between 449 and 473 [link], Sussex by Aelle and his three sons between 477 and 490 [link], the first king of Essex is listed in 527 [not ASC, so where?][link]. In 501 Porta and his two sons landed at Portsmouth and settled the Meon valley. Northumbria followed from 547 and Mercia in 584, although it is possible that some of the early Mercian history was suppressed in ASC for reasons of political stability at the time ASC was being written down, with the year 891 ending the original copying from the earlier ASC manuscript to ASC A. Mercia had fallen to the Danes and been recovered by Alfred as part of Wessex following the battle at Edington in 878. [The original version of ASC, sometimes referred to as the Early English Annals, appears to have been written during the reign of Alfred the Great, 871-899; it is thought that it was prepared in Wessex and probably not far from the Somerset-Dorset border.]

The timing of the establishment of the main British kingdoms

Note that there is more detail for the southern kingdoms

In 495 ASC records the arrival of two Ealdormen, Cerdic and Cynric, with five ships at a place called Cerdic's Ora (Shore) and says that on the same day they fought against the Welsh. Aethelweard adds that they were victors in the end. The site of Cerdic's original landing at Cerdic's Ora is generally taken to be Netley Marsh on the west side of Southampton Water. Thirteen years later, in 508, Cerdic and Cynric killed a British king called Natanleod and five thousand men at Cerdic's Ford (Charford on the Salisbury river Avon), after which all the land between Netley Marsh and Charford was named Netley. There was a further battle at Cerdic's Ford in 519 that has been associated [locate the reference] with an assault on Barbury Castle, attempting to gain control of the Roman road junction there and the Durotriges' trade route to Hengistbury. Barbury Castle is one of three contenders for the site of the battle of Mount Badon referred to by Gildas in his book De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (The Ruin and Conquest of Britain), which he is considered to have written some time between 480 and 550. He relates that the battle had stopped the Saxon advance from the date of his birth to the time he was writing and there was clearly such a pause in advance in this area.

Going back then to Cerdic and Cynric's landing in 495, we can follow these events in more detail, highlighted below in a translation of Aethelweard's Chronicle.

Aethelweard's Chronicle for 495 to 530, Old English Chronicles

Aethelweard's Chronicle for 530 to 540, Old English Chronicles

It is worth a brief aside here to show the rulers of Wessex, all kings except for Seaxburh from 672-673, the wife of Cenwahl, who ruled in her own right. The diagram shows how throughout this period succession passed to the next closely related eligible man able to lead his people into battle, and not generally from father to son. Careful reading of the sources suggests that at times there were up to five or six Wessex kings, so the line of descent shown is perhaps more sensibly thought of as being of the overlord of the time. The Saxon word kyne that evolved into the modern word king clearly didn't have its modern meaning in the early days, and a translation of chief or chieftain might be more appropriate, especially in 519, for instance.

Cerdic's family tree showing the rulers of Wessex from Cerdic to Alfred

The five kings set to the right of the diagram are from other family lines

.png)

The Ramsgate Viking ship: similar in concept but probably larger in scale than typical Saxon vessels [Photo: Wikimedia Commons]

The Viking ship pictured above represents a likely general design for the Saxon vessels used, although they would possibly have been rather smaller, with typical pictures showing perhaps 14 pairs of oars. Assuming one to an oar would make 28 rowers, so perhaps 30 or so per ship and a total force of 150 in the original landing party. It seems appropriate to assume that there would have been further arrivals, although the only one noted in ASC is the later arrival of Stuf and Wihtgar with the West Saxons in 514.

[The earliest Saxon boat is the Nydam in Denmark, 23 metres long by about 4 wide and dating from 310-320 [Wikipedia. The Sutton Hoo burial [[working here]] Wikipedia]

Cerdic arrived with his son Cynric, his constant companion in these early accounts and successor as king of Wessex in 534. Cerdic was described as an Ealdorman and had a British name. Some people wonder whether he was actually a British Saxon from further along the coast, perhaps Sussex. That he didn't have expansionist territorial aspirations in quite the same way as the Kentish Jutes or Sussex Saxons is apparent, although this could just have been circumstantial. It seems very probable that their families followed once a beachhead had been established.

We know from the early accounts that in Kent Hengist and Horsa worked with Vortigern to bring in more and more Jutes until they were able to drive Vortigern and his British people out of Kent. In Sussex Aelle started with a foothold probably at Selsey, and had worked his way right along to Pevensey in just 13 years. Was this because they were needing land for their compatriots or perhaps because the Britons fought back and this was the only way to remove the opposition? Both Sussex and Kent must have needed a constant flow of boatloads of new immigrants to occupy and hold the newly gained areas, a process described in great detail for Kent. Early Saxon place names in Kent and Sussex confirm the rapid expansion in those areas, just as in the Southampton area they confirm a slow initial settlement phase.

So after the initial battles some form of peace seems to have been established with the native Atrebates allowing the development of settlements and farming in the area. Looking at the map below of the early Saxon place names in this area it is tempting to suspect that such a boundary might well have followed the Roman Roads round the head of Southampton Water.

.jpg)

The sites of early Saxon settlements ending in -ing in the Southampton area

Note the proximity of all the yellow "-ing" pins to the surrounding Roman roads (red)

[Add Saxon coastline at Southampton and Selsey]

The map below will be shown several times. At this date we're just interested in the black lines and annotation that show three local arrivals: the South Saxons in 477, Cerdic and Cynric in 495 and Port in 501, together with the presumed West Saxon boundary up to 507.

Wessex boundaries up to 507 then in 508

Cerdic and Cynric then pressed on to Charford on the river Avon near Fordingbridge in 508. Whether they occupied the land beyond as far as Bokerley Dyke at the same time is unknown, although on these maps above I've shown it as occupied in the later battle at Charford in 519.

In 508 Cerdic and Cynric killed a British king whose name was Natanleod and five thousand men with him after whom the land as far as Charford was named Netley (ASC A and E).

514 The West Saxons Stuf and Wihtgar came to Britain with three ships at the place that is called Cerdic's Shore and fought against the Britons and put them to flight (ASC A and E).

Stuf and Wihtgar were brothers and were cousins of Cynric (Cerdic's nephews), which suggests strongly that they came by invitation and not by chance. The Saxons don't appear to have taken wives from among the native population, so we might imagine that contact with their home populations on the continent had been maintained throughout this period.

519 Cerdic and Cynric succeeded to the kingdom of the West Saxons and the same year they fought against the Britons at the place they now name Cerdic's Ford (Charford on the river Avon). And the family of the West Saxons ruled from that day on.

This battle in 519 is one of three that are postulated as the site of the Battle of Mount Badon described by Gildas when writing between 480 and 550. In it the Saxons were beaten and a peace established between Saxons and Britons that lasted for a generation. Gildas points out that the battle took place in the year of his birth and that he was now aged 44 years and one month [Gildas p313]. Historians have suggested that Cerdic was attempting to cut the Roman Road crossroads at Badbury Rings to deny the Britons the use of the harbour at Hengistbury Head. Badbury Rings lies just 11 miles along the Old Sarum Roman Road from the most westerly point of the Bokerley Dyke fortifications, so this objective is certainly plausible.

.jpg)

Badbury Rings

2018 Google.jpg)

The location of Badbury rings

Denied the chance to expand eastwards by the Durotriges and held back from moving north by the Belgae, the ensuing 33 years from 519 to 552 seem to have been devoted to internal consolidation. The areas occupied by the Jutes in the Meon Valley, New Forest and Isle of Wight became part of Wessex during this period, although whether by peaceable agreement or force wasn't recorded, with the exception of the Isle of Wight, which was taken by force in 530. The Roman Fort at Clausentum (Bitterne) was taken about 500, but abandoned rather than used.

The early days of the Jutish settlement aren't recorded either, but the Anglian, Saxon and Jutish communities of the country seem to have retained their identities very late into the Anglo-Saxon period. Bede, writing in 731 and then aged about 59, stated that Jutes settled in the places listed below, and Aethelweard's Chronicle (975-983) describes these same areas.

The map below is for a much later date but illustrates this probable geographical distribution of the Jutes.

.gif)

Distribution of Saxons, Jutes, Angles and Britons for a later date

Many sources [ref] quote the Jutes taking the Isle of Wight at roughly the same time as Kent, but I have never managed to locate any direct reference to its occupation before 530. Bede mentions Stuf and Wihtgar arriving with the West Saxons in 512, while ASC puts this date at 514. There have been many attempts to reconcile and restructure the dates from the various sources! Cerdic and Cynric took the Isle of Wight in 530 and the ASC entry mentioning Cerdic's death in 544 also says that "they" gave all of the Isle of Wight to Cerdic's nephews Stuf and Wihtgar, so I prefer to assume that the Isle of Wight was indeed taken and occupied by the Jutes (Stuf and Wihtgar, as Cerdic's nephews and Cynric's cousins implies presumably that Cerdic's sister had married into a Jutish family back home).

The same lack of definite references applies to the Meonwara. Some sources suggest that Port established the Meonwara after arriving at Portsmouth in 501, while others that the Meonwara were already there before the 495 arrival of Cerdic and Cynric at Southampton. I've found no supporting evidence for the latter. That the Ytene in the New Forest occupied only the south part of the New Forest seems generally agreed. Some sources say the Meonwara extended across the New Forest to Beaulieu/Lymington, with the Ytene to the west of the Beaulieu rive. The earlier definition of the King's Forest and later New Forest may help in resolving this.

The text below is by Kelly Kilpatrick 2014 and considers the likely area occupied by the Meonware based on place name study.

[reference: Saxons in the Meon Valley: A Place-Name Survey, Dr Kelly A. Kilpatrick Institute for Name-Studies, University of Nottingham,

This research is made freely available and may be used without permission, provided that acknowledgement is made of the author, title and web-address. local copy of paper, also available on the Saxons in the Meon Valley website.]

The post-Roman history of the Meon Valley region is of particular importance in the study of early Anglo-Saxon Britain. In his Historia Ecclesiastica (c. 731), Bede describes the Anglo-Saxon migration as consisting of three peoples, the Saxons, Angles and the Jutes (Iutae). According to Bede (I.15), 'From the Jutes are descended the people of Kent, and the Isle of Wight, and those also in the province of the West Saxons who are to this day called Jutes, seated opposite the Isle of Wight'. Yorke (1989: 90) demonstrates that the location of the mainland 'Jutish province' of Hampshire lay between Lymington and Hayling Island (see Insley 2001: 475). The River Hamble was in the territory of the Jutes (Bede IV.16), and place-names containing the ethnic name *Yte 'Jutes' allow us to visualise the probable extent of Jutish territory in Hampshire. Place-names with *Yte- are found near the proposed boundaries of the 'Jutish province', suggesting they were coined by neighbouring Saxons (Yorke 1898: 91-2; Sørensen 1999: 238). This element is preserved in Yting stoce, modern Bishopstoke on the River Itchen (Insley 2001: 475), and also in the early name of the New Forest, recorded in the twelfth century chronicle of John of Worcester (attributed to Florence of Worcester) as prouncia Iutarum in Noua Foresta and Ytene, meaning 'of the Jutes' (Insley 2001: 475; Yorke 1989: 90-1). The Meon Valley, therefore, was in Jutish territory (Sørensen 1999: 238). This is further suggested by the lost place-name Ytedene 'valley of the Jutes', which was located near East Meon (Yorke 1989: 90), and which likely marks their eastern border (Sørensen 1999: 238). Bede refers to the people of the Meon Valley as Meonware, for which see below; Klingelhöaut;fer (1992: 103) observes that valley names were often 'the identifying part of the territory/folk name'. Bede's use of prouincia [province] also implies that the Meonware formed an early political territory (Yorke 1989: 91). The Jutish region of Hampshire, including the Meonware, came under West Saxon control in the later part of the seventh century, although the evidence suggests that the Jutish identity of the region persisted for some time (Insley 2001: 474).

530 Cerdic and Cynric took the Isle of Wight and killed a few men at Wihtgar's stronghold. [Changed later, probably after the document had gone to Canterbury, to "many" in ASC A, but ASC B and C, Asser and Florence also read "a few".]

534 Cerdic passed away and his son Cynric continued to rule for 26 years. They gave all of the Isle of Wight to Stuf and Wihtgar.

Stuf and Wihtgar (here as Whitgar) as described in Asser's Life of Alfred, Old English Chronicles

Wessex in 530 - the blue line

By the time of his death in 544 Cynric had established a secure kingdom, but it fell to his son Cerdic to start its serious expansion northwards. The breakthrough came in 552 with the capture of the hillfort of Old Sarum, followed in 556 by the capture of Barbury Castle near Marlborough/Swindon. This brought the West Saxons into contact with their compatriots the Gewisse in the Thames valley, and the whole area became Wessex. Cerdic remained in charge until 560, when he was succeeded by his son Ceawlin, who had already featured alongside his father in the battle in 556.

The northward expansion through Old Sarum (552) and Barbury Castle (556)

552 Cynric fought against the Britons at Searo Byrg (Sorbiodunum, Sarum) and put the Britons to flight.

.jpg)

Old Sarum hillfort

556 Cynric and Ceawlin fought against the Britons at Beran Byrg (Barbury Castle) on the Marlborough Downs.

.jpg)

Barbury Castle between Swindon and Marlborough

Ceawlin 560-592 followed Cynric as king of Wessex.

.jpg)

Places mentioned in ASC relating to Ceawlin 556-590

Ceawlin first expanded eastwards towards London in 568 and took Lenbury (Limbury), Aylesbury, Benson and Bedford in 571. In 577 they turned westwards, remaining north of the Wansdyke defence line of the Durotriges, and took Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath. This was a decisive move as it separated the Welsh and Cornish Britons and gave the West Saxons access to the Severn estuary. It brought the whole of the kingdom of the Hwicce under Wessex control, this having earlier been the territory of the Dobunni Iron Age tribe.

The kingdom of the Hwicce, taken by Wessex in 577 and controlled until it was taken from them by Mercia in 628

(Wychwood Forest included until 679)

Wessex expansion 552-584 and retraction 591-592

Up to this time the battles had been entirely between the West Saxons and Britons, but now things started to become more complicated, with warring between rivals within Wessex and even seeming to include Britons and West Saxons fighting together against other West Saxon parties.

592 This year there was a great slaughter of Britons at Woden's Barrow [Swindon] and Ceawlin was driven from his kingdom (by his nephew) Ceol. [Aethelweard puts 584, great slaughter on both sides, Ceawlin put to flight and died a year later]. Ceol reigned five or six years according to the sources.

In 592 Ceawlin was defeated in a battle at Wodnesbyrg (Woden's Barrow now Adam's Grave near Alton Priors) by his nephew Ceol, or possibly Ceol and the Britons (Durotriges) acting together. Woden's Barrow lies in Durotiges territory three quarters of a mile south of where Wansdyke crosses the ridgeway and the mention of Ceol, Ceawlin and Britons has been taken to suggest that the Britons and Ceolric may have been acting together against Ceawlin. Ceawlin died the following year. Whether Wessex and the Gewisse parted company for the duration of the next two reigns or remained as a single entity is difficult to determine. ASC A shows Ceol ruling from 591, the year before it records this battle taking place. Ceolric was succeeded by Ceolwulf in 597 who "continuously fought and strove against the Angles (Mercia), Welsh and Picts, or against the Scots". That said, his only recorded battle was against the South Saxons, possibly over control of the Isle of Wight and south Hampshire.

Woden's Barrow / Adam's Grave is south of Wansdyke in Durotriges territory

Yellow = Wansdyke, Blue = river Avon, Red = Roman roads

(c)2018 Google, Image (c)2018 Getmapping.plc, Image (c)DigitalGlobe

.png)

Woden's Barrow / Adam's Grave is south of Wansdyke in Durotriges territory

Source history.wiltshire.gov.uk

.gif)

Woden's Barrow / Adam's Grave detail

Source HistoricEngland.org.uk

2018 Google, Image (c)2018 Getmapping-plc.jpg)

Woden's Barrow / Adam's Grave detail

(c)2018 Google, Image (c)2018 Getmapping-plc

The Saxons were pagans and had swept Christianity away in the areas they invaded, but we should remember that the Britons, with their Roman legacy, were still Christians. Augustine came to Kent in 601 and sent a bishop to Essex in 604, but as he had made little further progress in thirty years, the pope sent Birinus to Britain in 634. His plans lay further north, but finding most confirmed pagans (paganissimos) in Wessex, stayed to convert people here. This timing means that the Saxons had been converted before taking the west country, ensuring the continuity of Christianity there from Roman times. Where Augustine had attempted to assert authority over the British bishops in the areas around Kent and thereby alienated them, Birinus acknowledged the British bishops as equals and invited them all to participate with him at important events, with great success.

652 saw the beginning of a final assault on the Durotriges, an event that had been 157 in the making since Cerdic and Cynric had landed and attempted to move west. A battle took place at Bradford on Avon in 652 and then in 658 Cenwahl drove the Durotriges back to the river Parret in Somerset. Their Wansdyke defence line had finally been breached. There were a number of occasions on which a new Wessex king turned his attentions west and lost ground in the east at the same time and this was one such, with Mercia taking the Meon valley and Isle of Wight in 661 and giving them to the king of Sussex. This change was shortlived, as the earlier boundary was back in place by 694.

Wessex in 661

In 686 Caedwalla of Wessex attacked the Isle of Wight and killed the king and all his family with the exception of his sister, wife of the king of Kent [Ref Bede p252, written about 731]. The royal family of the Isle of Wight were all killed, although were given space to be converted and baptised first. All that is, except the king's sister, the wife of the king of Kent. There were ramifications! Ironically, of course, these were the descendants of Stuf and Wihtgar, given control of the Isle of Wight by Cerdic in 530.

Ine, 688-726, took the rest of Somerset and Devon and went on in 694 to issue his law code. This is the earliest surviving Anglo-Saxon law code outside Kent (602-3) and was probably compiled alongside Wihtred of Kent's new law code, issued the following year on the 6th September 695 [Wikipedia Ine]. The Saxon town of Hamwic at St Mary's Southampton was a prominent and thriving community and port at this time, although it was abandoned as being too vulnerable to seaborne attack in a later period.

Wessex under Ine in 694 [change filename, which is erroneously 794)

In the same way as the local Wessex kings vied at times for power, so did the rulers of the main Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, once all available British areas had been absorbed. Dorchester on the river Thames and the earlier seat of the Gewisse changed hands repeatedly between Mercia and Wessex. The earlier kingdom of the Hwicce forms a useful example of one of these changes, being taken by Wessex for a time, then by Mercia, and this contributes to Mercia's complex story of the spread of Christianity in the area. Sussex, Kent, Surrey and Essex were under Wessex control in 685-686 but were lost again in 688-726 and during the Mercian Hegemony Wessex fell under Mercian control for 15 years between 730 and 745 and for a further 20 years at the end of the century from 781 to 802.

Kingdom of the Hwicce, with Wychwood Forest outlined lost by 679

Areas under Wessex control from 685-686, but lost again in 688-726

The Mercian period of dominance 730 to 796

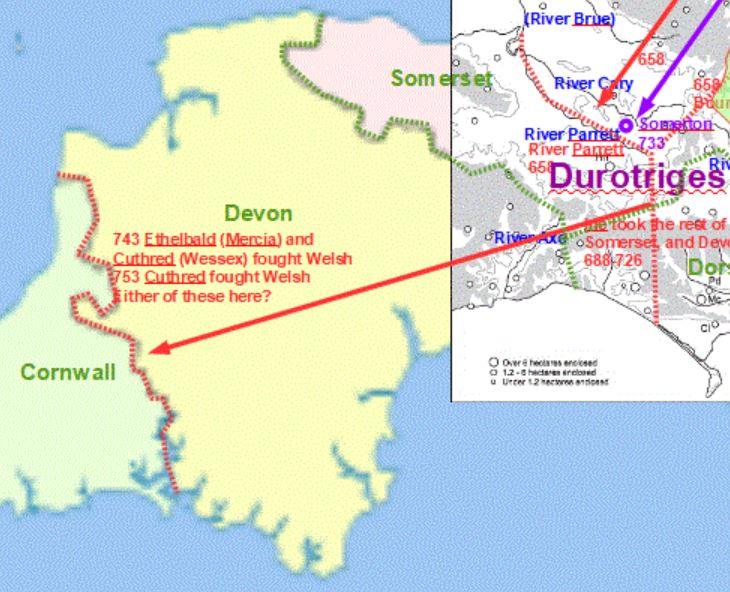

In 742 and 753 the Cornish still maintained the 726 boundary), but by 839 Cornwall came under the control of Wessex.

The battle for supremacy continued. Egbert of Wessex (802-839) defeated the Mercian king Beornwulf in 825 then Wiglaf restored Mercian independence five years later in 830. However, Wessex was now the dominant power in England [Wikipedia Mercia]. 883-911 saw Mercia under Wessex overlordship, although the Danes took the eastern part of Mercia in 877. From 879 all Mercian coins were in the name of the West Saxon king.

The English Kingdoms in 839 with Sussex, Kent and Essex under the control of Wessex

While Cornwall was under the overlordship of Wessex, it was not incorporated into Wessex.

787 saw the first of the Danish raids, with a few sporadic attacks up to Lindisfarne in 793 including one at Portland Bay in Dorset. An attack on Jarrow in 794 led to the crews being killed and this seems to have resulted in a gap of about 40 years before raids resumed. Significant raids started in 833 and 835, with 35 ships in the first of these - and these would have been the larger style of ship pictured earlier. Raids became more frequent and by the time the Danes started overwintering in Britain in 851, substantial damage was being inflicted widely across the country. This turned into a concerted attack on Britain in 865.

The Danes - 870 to their defeat in 878

In 865, the same year as Aethelred's succession as king, a great Viking army arrived in England, intent on conquering the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Within five years they had destroyed two of the principal English kingdoms, Northumbria and East Anglia. Mercia was also taken by 874, leaving just Wessex still under Saxon control. Wessex was attacked in 870-874 then again in 875-878. Having been driven back to Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, Alfred and his family took refuge in the Somerset marshes after the battle on 6th January. Alfred worked hard and effectively to build up a system of local militias able to take on the rapidly moving raiding parties, and longships able to overtake the shorter Viking ships. Just four months later and supported by levies from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire, he defeated the Danes at Edington. Significantly a force of 1200 Vikings landed from 23 ships intending to take him from the rear, but were dealt with by a local force, probably the first event of its kind, while the king fought at Edington. The treaty of Wedmore followed, whereby England was divided between the Saxons and the Danelaw. The Saxons gradually eroded the Danelaw, with England finally united as a nation under Aethalstan in 927.

.gif)

Wessex in 886

Wessex took almost 400 years from 495 to expand its boundaries to cover the country outside the Danelaw by 886.

Further sections are being prepared to go here; there are currently only a few notes on the remainder of this page.

From what has come down to us, Whiteparish must have started out as a number of minor settlements, from southwest to northeast Abbotstone (now Titchborne), Moore, Frustfield (probably Whelpley), Alderstone and Cowesfield Esturmy. [Link to each and to a discussion of early settlement patterns and development.]

Romsey Abbey was founded in 907 on what was probably a new site and the town almost certainly grew up around it after this date.

History of the English Language (web)Encyclopaedia Brittanica (beware the adverts and pop-ups)

History of the English Language (.pdf) from Encyclopaedia Brittanica, badly overwritten

History of the English Language (.odt) from Encyclopaedia Brittanica, clearer copy of content but with html markup included, best opened from the folder rather than from here